I had never fully gauged how much I associated the films of Ernst Lubitsch with the very notion of civilization until an evening in the immediate aftermath of the attacks of September 11. The occasion was a dinner in Paris, at the home of a French poet and his Italian wife; and it was through her graceful stewarding of the conversation that it turned away from the events of the day—and the unavoidable mood of shock, grief, anxiety, and disorientation—toward, of all things, Lubitsch. She had recently seen a screening of Angel (1937), and as we began to discuss the film in detail, and as memories of other Lubitsch films came welling up, I began to feel a gratitude to Lubitsch that was profound and personal, as if the emotional qualities he had embodied in his art possessed, even in mere recollection, the sort of healing power more commonly associated with the tombs of saints.

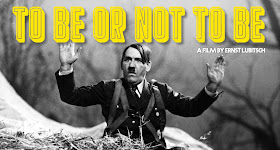

He had made a world of elegant illusions, of luxuries and pleasures savored by being transformed into metaphorical wit (the “Lubitsch touch”)—a parallel place that, at any time, might well be the place where one would rather be—but there was nothing flimsy or casual about it. The illusion was acknowledged to be an illusion by the characters themselves, and that acknowledgment made it real. Nowhere did this realness become more apparent than in To Be or Not to Be (1942), where for once he dared to pit the inhabitants of his world, living on wishful reverie and theatrical sleight of hand, against forces of real destruction. Jack Benny against the Nazis? A farce set in occupied Warsaw? Jokes about concentration camps? The Gestapo itself foiled by an elegant web of implausibilities? The victory that he permitted his creatures was the victory of art over life, and it was possible only as long as he did not compromise his own art in the least. It is not surprising that a good many critics and viewers at the time found the movie tasteless and inappropriate. The ever-astute Bosley Crowther of the New York Times intoned: “Frankly, this corner is unable even remotely to comprehend the humor.”

If only the film had been a bit more sentimental, the jokes might have gotten by; comic relief was something understood and accepted, and indeed was to become the bane of many a wartime melodrama. But To Be or Not to Be did something rare, then or at any time, by interweaving farce and disaster in such a rigorously structured fashion as to elicit, in the very same scenes, genuine anxiety and a hilarity so acute that it has something like an ecstatic kick. For many, myself included, it is close to being the funniest film ever made, featuring Carole Lombard in her last and greatest performance (she would be killed in a plane crash before the movie opened) and Jack Benny in the only film role that did justice to his comic genius. But at every step, it keeps plainly in view—just offscreen, and detectable even in the comic buffoonishness of Sig Ruman’s Colonel Ehrhardt—the possibility of real terror, real soul-destroying cruelty, real suffering. The fear is real, and even though each emerging danger is deflected by the most ingenious comic solution, another danger soon enough takes its place.

The story line of To Be or Not to Be is attributed to Lubitsch’s old acquaintance Melchior Lengyel, one of those Hungarians whose dramaturgical contraptions the director found so indispensable as a point of departure for his own inventions. (Lengyel had previously appeared in the credits of Lubitsch’s Forbidden Paradise, Angel, and Ninotchka.) It is hard to say how much the story matters here, since everything depends on the manner of the telling. As scriptwriter, Lubitsch enlisted not a previous collaborator, such as Samson Raphaelson or Billy Wilder, but the playwright Edwin Justus Mayer, author of the critically admired, commercially disastrous play Children of Darkness (1930), a work too literary for a Broadway hit and too dark, with its story of condemned prisoners in eighteenth-century London, for the comedy it was meant to be. To Be or Not to Be differs sufficiently from any other Lubitsch film that it seems fair to grant Mayer a decisive role in shaping its pointed style.

Almost no line of dialogue is without a barbed secondary implication; jokes comment knowingly on the jokes that preceded them, adding elements of ironic awareness too discreetly and rapidly for a single viewing to suffice. “I thought you would say that,” says Benny’s Joseph Tura (impersonating the turncoat Professor Siletsky) to Gestapo commander Colonel Ehrhardt when the colonel comes up with precisely the same remark that Tura improvised when impersonating Colonel Ehrhardt in conversation with the real Professor Siletsky. Earlier, Lombard, as Tura’s wife, Maria, rattles off examples of how her husband is always trying to take credit for everything, concluding: “If we should ever have a baby, I’m not sure I’d be the mother.” Benny’s even funnier comeback—“I’m satisfied to be the father”—subverts Production Code niceties neatly but is often missed because audiences are still laughing at Lombard’s impeccably delivered speech.

Not to suggest that anyone but Lubitsch could dominate a Lubitsch production. As Robert Stack, who plays the love-struck young Polish aviator Lieutenant Sobinski, remarked: “He was a Renaissance man. He could do it all. He was an actor, a writer, a cameraman, an art director. He did not allocate responsibility.” In To Be or Not to Be, he seems to deliberately challenge the stylistic and emotional equilibrium of his earlier work, as if to see how much stress it can take. By way of preparing the audience for what is in store, he lays down from the start a pattern of deception and reversal. We see Hitler walking the streets of prewar Warsaw; a moment later, we are given Jack Benny in the role of a Gestapo officer—something so shockingly unexpected that Benny’s own father, unprepared, walked out of the theater in disgust.

These first impressions are rapidly dissipated as we are made aware of having been drawn into a play within a play. But the structural game playing continues in different modes, as theatrical illusion is enlisted in the struggle against the Nazis, whose own grandiose brand of theatricality has a heavy-handed humorlessness that will be successfully manipulated by Benny, Lombard, and the rest of their troupe of Polish actors. The genius of the film is that the actors do not work as a buoyant, Merry Men–style band of movie adventurers but as a squabbling assortment of egotists and grumblers who needle one another even in the midst of danger, ham actors (“What you are I wouldn’t eat,” Felix Bressart’s Greenberg tells Lionel Atwill’s Rawitch) who cannot resist padding their lines even when carrying out an undercover mission against the Gestapo. From first to last, this is a film about theater, weaving in countless notes on the perils and uneasy joys of improvisation and impersonation, and relishing with infinite affection the many shades of actorly vanity.

These first impressions are rapidly dissipated as we are made aware of having been drawn into a play within a play. But the structural game playing continues in different modes, as theatrical illusion is enlisted in the struggle against the Nazis, whose own grandiose brand of theatricality has a heavy-handed humorlessness that will be successfully manipulated by Benny, Lombard, and the rest of their troupe of Polish actors. The genius of the film is that the actors do not work as a buoyant, Merry Men–style band of movie adventurers but as a squabbling assortment of egotists and grumblers who needle one another even in the midst of danger, ham actors (“What you are I wouldn’t eat,” Felix Bressart’s Greenberg tells Lionel Atwill’s Rawitch) who cannot resist padding their lines even when carrying out an undercover mission against the Gestapo. From first to last, this is a film about theater, weaving in countless notes on the perils and uneasy joys of improvisation and impersonation, and relishing with infinite affection the many shades of actorly vanity.

It is fascinating to contemplate To Be or Not to Be alongside that other great exposition of theatrical egomania, Howard Hawks’s Twentieth Century (1934), especially given the presence of Carole Lombard in each, giving two utterly different performances. With Hawks, the atmosphere is one of real madness, a self-absorption so relentless on the part of both Lombard and John Barrymore that it achieves a mood of unforgiving savagery. Nothing could be further from that nightmare than the vanity of Lombard and Benny in To Be or Not to Be, in which each indulges as the sort of illusion that makes life bearable, and that each in turn tolerates in the other. They are more, not less, human by virtue of their egotism, since neither evinces any desire to hurt. As the devil says to Don Ameche at the end of Heaven Can Wait (1943), Lubitsch’s next film: “We don’t cater to your sort here.”

Such is the concision of the screenplay that to summarize the plot of To Be or Not to Be—to relate precisely how it becomes necessary for Carole Lombard to promise to spend the evening with the traitorous Professor Siletsky to prevent him from betraying the Polish resistance movement, and for Jack Benny to impersonate in turn Colonel Ehrhardt and Siletsky (the real Siletsky having just been assassinated on the stage of Benny’s theater), to explain how Tom Dugan’s Bronski, the Hitler impersonator of the opening scene, finally gets his longed-for chance to play the part he has rehearsed for—would take nearly as long as the film. Nothing is wasted here, although much is repeated. In fact, the rhythm is built through the repetition of elements, the same scenes replayed with different actors, the same lines spoken again in different contexts.

Long acquaintance with To Be or Not to Be only makes more fascinating the skill with which these variations are worked: the title soliloquy itself, the joke about Hitler becoming a piece of cheese, the Shylock speech, the false beards and mustaches, not to mention the countless comic inflections given to “Heil Hitler.” That phrase almost becomes the leitmotif of the film; not only does Lubitsch turn it into a comedy line, he turns it into an array of quite distinct comedy lines, having already kicked the film off with Bronski’s hilarious entrance as Hitler in the Tura company’s never-to-be-performed play Gestapo: “Heil myself.”

The bedroom farce that centers on Benny as “that great, great actor Joseph Tura,” Lombard as his wife, and Stack as her doting young admirer will not be resolved by the war that so jarringly interrupts it, merely deferred to a sequel we can only imagine, and for which the last shot sets us up. “It’s war!”: the Lubitsch comedy is disrupted, for once, by forces beyond its control. Left to follow its own course, it might have turned the film into a close variation on his previous picture, the only sporadically successful triangular comedy That Uncertain Feeling (1941). Under the circumstances, it goes underground, like the actors, but pops up at the most inopportune moments, as when Benny’s simmering jealousy nearly destroys the mission when, impersonating Colonel Ehrhardt, he takes advantage of the role to try to find out what Maria has been up to. The spark of inappropriate feeling gives him away to Professor Siletsky, and the mood suddenly darkens as Siletsky comes as close as the Production Code would allow to calling Tura’s wife a whore. The rules of discretion normally operative in Lubitsch comedy have been shattered by a character beyond civility and beyond humor.

Professor Siletsky is crucial to the film because he is the only character who is not funny. The other Nazis in the story can be fooled. Ruman’s magnificent Colonel Ehrhardt is a full-blown comical picture of evil—obsequious to superiors and tyrannical to underlings, lecherous and fatuously self-admiring, quick to bully and quicker to plead for mercy—and even his ending is played for comedy. Siletsky is a figure of real evil and has to be killed outright, with no jokes. Everything that surrounds him is in earnest, giving a particularly sharp edge to the scene in which Maria visits him in his hotel room to intercept his exposure of the Polish resistance network. As William Paul points out in a brilliant passage in his book Ernst Lubitsch’s American Comedy, the scene is full of echoes of Lubitsch’s 1932 Trouble in Paradise. There, Miriam Hopkins and Herbert Marshall were two con artists, each vainly trying to con the other and finally falling in love. In To Be or Not to Be, all the elegance of that earlier seduction scene is reduced to a crude bit of sexual bargaining, with Maria playing for time by keeping the professor at bay.

Siletsky’s tired imitation of a suave seduction does indeed suggest that he saw Trouble in Paradise at some point and picked up a few line readings from Marshall, but just underneath that is brutal impatience and barely veiled contempt. The Nazi as would-be bon vivant comes out with lines like “In the final analysis, all we’re trying to do is create a happy world . . . Why don’t you stay here for dinner? I can imagine nothing more charming, and before the evening is over, I’m sure you will say, ‘Heil Hitler.’” There is no suggestion, however, that Siletsky has any ideological concerns other than being on the winning side. Where many Hollywood films would emphasize Nazi fanaticism, Lubitsch zeroes in on a more disturbing image of pragmatic calculation. Siletsky is an intruder in Lubitsch’s comic world, the voice of someone who has come to announce that the party is over.

It is precisely in this scene that Lombard’s playing reaches a giddy peak of exhilaration. She proves Maria Tura is a great actress because she’s sexiest at just the moment where we know she’s totally faking it; surely Siletsky will be captivated, because we certainly are. She brings to an impossible part—a Polish patriot prepared to sell out her country for a serving of oysters and caviar, a famous actress who finds the attentions of an aging Gestapo collaborator irresistible—all the invention and exuberance she can muster, spinning fresh revelations of flirtatious charm on the edge of the abyss to gain a little more time, right up to that final, breathless “Bye!” she whispers to Siletsky as she glides out the door.

I had a chance to experience the film’s power again not long ago, under circumstances peculiarly fitting, at an informal screening of it with other fellows of the American Academy in Berlin. The academy is situated in the Wannsee quarter, in a villa across the lake from that other villa where, at the Wannsee Conference of 1942, the administrative details of the Holocaust were ratified by Reinhard Heydrich, Adolf Eichmann, and others. The academy villa, formerly the home of a Jewish industrialist, was seized by the Nazi regime and became the residence of Hitler’s finance minister, Walter Funk. No one else attending the screening had seen the film before, and it was exhilarating to feel both their astonishment that this film had been made at all and their hilarity as it unfolded. All of us experienced an extra frisson from seeing it in an ornate library once allocated to a functionary of the Third Reich.

Hitler is said to have had a particular animus against Lubitsch, as a Berlin Jew who triumphed in the German film industry and then went on to further triumphs in Hollywood. Lubitsch’s face is used in the Nazi propaganda film The Eternal Jew (1940) as an archetype of corruption and depravity, employing footage of the director taken in Berlin on his last visit to his hometown, just six weeks before Hitler was sworn in as Reich chancellor. No filmmaker, indeed, is more immune to the appeal of martial and nationalistic grandiloquence. He is a heroic champion of the unheroic, a tailor’s son who sees in all variations of royal and aristocratic authority nothing more than an opportunity for humor, a defender of the small virtues of politeness and shared pleasure who managed, if not to wake from the nightmare of history, then at least to make a counterdream in its midst.

The vibrance of Lubitsch’s domain is in its freedom from contempt or triviality or easy escapism or indifferent sentimentalism—freedom, against all odds, from bitterness. We may well infer from his films a deep conviction that power, and fantasies of power, however disguised, are the poison of human existence, separated by a chasm from the venial and eminently forgivable flaws of ordinary lust and ordinary vanity. Lubitsch, of course, would never be so strident as to say so out loud. What he shows us is an illusion, but an illusion created from a refined consciousness of what the world is, with the aim of creating delight. In To Be or Not to Be, he achieved this even in the face of the darkest of shadows. In any situation, as Greenberg observes early on, “a laugh is not to be sneezed at.” --Criterion

No comments:

Post a Comment